FAQs

Veterinary Medicine

What roles do veterinarians play in society and what are their duties on the job?

Veterinarians are at the forefront of protecting the public’s health and welfare as they play a major role in the health of our society by caring for animals. They also use their expertise and education to protect and improve human health. It’s likely that you are most familiar with veterinarians who care for our companion animals, but there are many other opportunities for veterinarians. Veterinarians also help keep the nation’s food supply safe, work to control the spread of diseases, and conduct research that aid both animals and humans. There is a growing need for vets with postgraduate education in particular specialties, such as molecular biology, laboratory animal medicine, toxicology, immunology, diagnostic pathology or environmental medicine. The veterinary profession is becoming more involved in aquaculture, comparative medical research, food production and international disease control.

Veterinarians who work directly with animals use a variety of medical equipment, including surgical tools and x-ray and ultrasound machines. They provide treatment for animals that is similar to the services a physician provides to treat humans. Veterinarian duties include:

-Examine animals to diagnose their health problems

-Treat and dress wounds Perform surgery on animals

-Test for and vaccinate against diseases

-Operate medical equipment, such as x-ray machines

-Advise animal owners about general care, medical conditions, and treatments

-Prescribe medication

-Euthanize animals

Adapted from https://hpa.princeton.edu/sites/hpa/files/veterinarymedicine-2018.pdf, https://hpa.princeton.edu/explore-careers/veterinary-medicine

What careers are available in the veterinary medicine field?

The following list is not exhaustive but provides an overview of careers where graduates of veterinary medical schools can effectively apply their Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) degrees.

-General private practice as standard veterinarian

-General public practice in shelter medicine and community medicine

-With advanced training and experience, practice a specialty field such as ophthalmology, orthopedics, aquatic animal medicine, marine biology, wildlife animal medicine, zoo medicine, or emergency animal medicine.

-The Federal Government employs veterinarians through the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) working on biosecurity, environmental quality, public health, meat inspection, regulatory medicine, and agricultural animal health, or the investigation of disease outbreaks.

-Research, either in a university setting or with companies that produce animal-related products or pharmaceuticals, as laboratory medicine veterinarians and veterinarian-scientists

-Public Health, particularly with governmental agencies such as the United State Public Health Service, which works to control the transmission of animal-to-human (zoonotic) diseases.

-Global Veterinary Medicine, in private practice or with international agencies working in areas such as food production and safety or emerging diseases.

-Public Policy, working for governments and non-profit organizations on animal and zoonotic diseases, animal welfare, public health issues, or as consultants with non-governmental agencies.

Adapted from https://hpa.princeton.edu/sites/hpa/files/veterinarymedicine-2018.pdf

I love animals. Should I pursue veterinary medicine?

Today’s veterinarians are extremely dedicated to protecting the health and well-being of animals and humans. Veterinarians are animal lovers and understand the value of animals in our families and society. However, being an animal lover is simply not enough to be admitted to vet school. There are a plethora of potential careers for animal lovers including being a zoologist, kennel attendant, humane educator, marine biologist, veterinary technician, marine biologist, and wildlife rehabilitator. Ask yourself: why am I drawn to vet medicine? What qualities do I possess that would help me become a successful vet? How do I see myself contributing to the field and my community as a future vet? Gaining experience by volunteering or working at a veterinary clinic/hospital and directly working with vets should help inform your decisions regarding a veterinary medicine career. It is also essential for aspiring vets to possess other personal attributes that contribute to a successful career in veterinary medicine. These include:

–A Scientific Mind: A student interested in veterinary medicine should have an inquiring mind and keen powers of observation. Aptitude, interest, and doing well in the biological sciences is important.

–Good Communication & Interpersonal Skills: Veterinarians must meet, talk, and work well with a variety of people.

–Compassion: Being compassionate is an essential attribute for success as it should guide humane treatment and medical decisions by a veterinarian. It is also important for veterinarians working with owners who form strong bonds with their animals.

–Leadership Experience: Many environments (e.g., clinical practice, governmental agencies, public health programs) require that veterinarians manage employees and businesses. Having basic managerial and leadership skills contribute to greater success in these work environments.

Adapted from https://hpa.princeton.edu/sites/hpa/files/veterinarymedicine-2018.pdf

I love money. Should I pursue veterinary medicine?

A harsh reality that pre-vets should be aware of is although vet school is as expensive and time-consuming as medical school, the economic return is one of the lowest in the healthcare industry. The average starting salary for Princeton grads is roughly about the average starting salary of vet school grads(~60-80k). 99% of the time, students who apply to vet school genuinely care about animals, are not in it for the money, and are willing to be broke for the job even after years of extra training. Financial struggles reportedly contribute to veterinarians having disproportionately high suicide rates in the healthcare field.

Vet school graduates may choose to pursue a specialty, which can give a salary boost, but specialization requires years of residency and internships with low pay all while paying off your loans. Location and type of practice can also impact salaries.

There is essentially very limited grant aid for vet schools (unlike some medical schools that are now beginning to cover full tuition for financial aid students) and it is probably because vet school graduates are too broke to afford large gifts to their vet school alma maters. There are some scholarships that students could apply to, but financial aid tends to be mostly in the form of loans and you are expected to work jobs during the summers and/or the academic year. However, attending your state vet school could help you get a somewhat reduced tuition charge for being an in-state resident.

Vet Schools

How is veterinary school different from medical school?

Vet school students deal with dozens of species while medical school students focus primarily on humans. The MCAT is usually not required unlike medical school and instead most require the GRE. While both require letters of recommendation, HPA committee letters are not required for vet school. Students take challenging courses in the biological sciences early on and participate in rotations later on in both vet and med school. One additional interesting difference is that vet schools have a set number of in-state seats and out-of-state seats, which means applicants are usually only competing with residents if they are residents or non-residents if they are non-residents for admission. Tuition is also substantially lower for resident students.

How many vet schools are there and where are they located?

As of Summer 2020, there are 32 American, 5 Canadian, and 16 international veterinary medicine colleges accredited by the AVMA (American Veterinary Medical Association). Accreditation may change for various reasons and lists are biannually updated here.

ACCREDITED COLLEGES IN THE UNITED STATES:

- Auburn University (Alabama)

- Tuskegee University (Alabama)

- Midwestern University (Arizona)

- University of Arizona (Arizona)

- University of California – Davis (California)

- Western University of Health Sciences (California)

- Colorado State University (Colorado)

- University of Florida (Florida)

- University of Georgia (Georgia)

- University of Illinois (Illinois)

- Purdue University (Indiana)

- Iowa State University (Iowa)

- Kansas State University (Kansas)

- Louisiana State University (Louisiana)

- Tufts University (Massachusetts)

- Michigan State University (Michigan)

- University of Minnesota (Minnesota)

- Mississippi State University (Mississippi)

- University of Missouri-Columbia (Missouri)

- Cornell University (New York)

- Long Island University (New York)

- North Carolina State University (North Carolina)

- The Ohio State University (Ohio)

- Oklahoma State University (Oklahoma)

- Oregon State University (Oregon)

- University of Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania)

- University of Tennessee (Tennessee)

- Lincoln Memorial University (Tennessee)

- Texas A&M University (Texas)

- Virginia-Maryland Regional College (Virginia + Maryland)

- Washington State University (Washington)

- University of Wisconsin-Madison (Wisconsin)

The following 22 US states currently do not have vet schools:

- Alaska

- Arkansas

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Kentucky

- Maine

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- North Dakota

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Utah

- Vermont

- West Virginia

- Wyoming

ACCREDITED COLLEGES IN CANADA:

- University of Calgary (Alberta)

- University of Guelph (Ontario)

- University of Prince Edward Island (Prince Edward Island)

- Université de Montréal (Quebec)

- University of Saskatchewan (Saskatchewan)

ACCREDITED COLLEGE INTERNATIONALLY:

- Murdoch University (Australia)

- The University of Sydney (Australia)

- University of Melbourne (Australia)

- University of Queensland (Australia)

- University of Bristol (England)

- University of London – Royal Veterinary College (England)

- VetAgro Sup (France)

- University College, Dublin (Ireland)

- Universidad Nacional Autonoma de México (Mexico)

- State University of Utrecht (The Netherlands)

- Massey University College of Sciences (New Zealand)

- University of Glasgow (Scotland)

- The University of Edinburgh (Scotland)

- Seoul National University (South Korea)

- Ross University (West Indies)

- St. George’s University (West Indies)

Is it easier to get into an in-state vet school than an out-of-state vet school?

It is very possible to make the case that it is usually relatively easier to get accepted to a vet school in your state than a vet school out of your state.

For example, Ohio State’s incoming Class of 2022 consisted of 66 residents and 96 non-residents and the school had received 245 resident and 1144 non-resident applicants. The acceptance rate for residents is 27% compared to 8% for non-residents. The difference is significant! However, these stats are not based off of all the students that were offered admission, including ones that declined acceptances.

University of Florida offered admission to 102 residents out of a total of 433 resident applicants and offered admission to 95 non-residents out of a total of 809 non-resident applicants for the Class of 2023. This amounts to a 24% acceptance rate for residents, double that of the non-resident acceptance rate (12%).

As a final example, UCDavis offered admission to 128 residents out of a total of 510 resident applicants and offered admission to 6only 20 non-residents out of a total 502 non-residents applicants. This amounts to a 25% acceptance rate for residents and only a 4% acceptance rate for non-residents. Admitted residents also had much lower science GPAs on average (3.62) compared to non-residents (3.96).

Our final verdict is: where you live can definitely impact your chances of getting accepted into vet school. However, you can’t just pack your bags right before submitting your application and move to the state with your dream vet school. Applicants have to submit proof of residency for at least a certain amount of time (usually 1-2 years) in order to be considered residents.

There are still 22 states without vet schools. So the question that remains is: are those students at a disadvantage? While not entirely clear, some states without vet schools like New Jersey sign contracts with states that do have vet schools to reserve a set number of seats and discounted tuition rates for students. If you are located in one of the 22 states, research whether your state has similar to New Jersey’s policies as shown below:

The Veterinary Medical Education Act of 1971 provides for contractual agreements between the New Jersey Department of Higher Education and out-of-state schools of veterinary medicine for the acceptance of New Jersey residents who are and have been residents of the state of New Jersey for 12 consecutive months. Under the terms of the act, the schools receive a substantial subsidy toward educational costs in return for a number of guaranteed reserved seats, at in-state tuition and/or reduced fees, for New Jersey residents. At present, New Jersey has contractual agreements with the following schools: New York State College of Veterinary Medicine of Cornell University, University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Tufts University, Iowa State University, Kansas State University, Oklahoma State University, and Tuskegee University School of Veterinary Medicine, all of which reserve seats for New Jersey residents. As of 2003, 24 spaces were available. Students are encouraged to apply to all of these institutions in order to increase their chances of acceptance. Most schools of veterinary medicine also admit a few out-of-state residents without specific contracts.

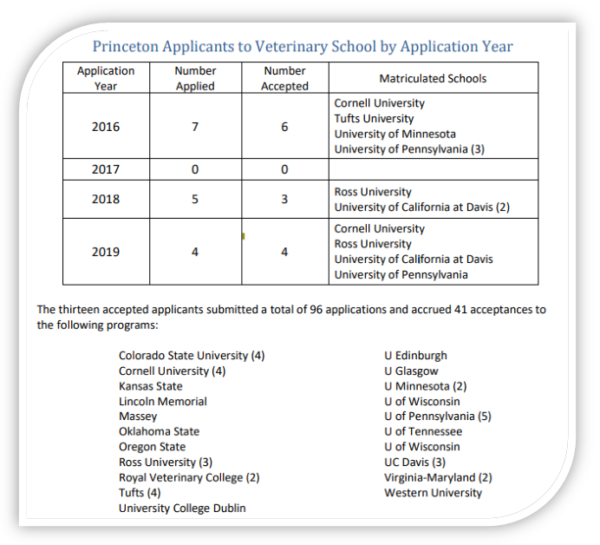

What schools have Princeton students have recently applied to and matriculated at?

According to HPA, the following vet schools received the most applications from Princeton students from 2012-2016:

- Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences

- Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine

- North Carolina State Veterinary Medicine

- Tufts University Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine

- University of California Davis School of Veterinary Medicine

- University of Minnesota-Twin Cities College of Veterinary Medicine

- University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine

- University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine

Princeton students have matriculated at the following schools from 2012-2016:

- Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine

- North Carolina State Veterinary Medicine

- Tufts University Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine

- University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine

HPA has now released more updated, in-depth data from the past four application cycles:

Applying to Vet School

Being Pre-vet at Princeton

Does Princeton have a veterinary program or major?

Princeton does not have a pre-veterinary program or major. While pre-vets at Princeton join a variety of STEM and humanities departments, many choose to concentrate in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, which is arguably the closest department to veterinary/animal science.

Does Princeton offer pre-vet advising?

Princeton HPA (Health Professions Advising) does not have advisors designated specifically for pre-vet students, but HPA staff still advises all pre-health students including pre-dental and pre-vet students. Meet with HPA as early as you can for advice and assistance. You can also contact hpa@princeton.edu and prevet@princeton.edu to join both the HPA and pre-vet listservs for additional support. See more information from HPA below:

Answer: Thanks for checking in with us! It’s true that there aren’t many pre-vet students on campus, but we certainly enjoy working with pre-vets. We have specialized listservs for pre-vet, pre-dental, and MD/PhD through which we share targeted messages, so be sure to email Jen at HPA@princeton.edu and ask that she put you on the pre-vet email list. Most often, we answer pre-vet students’ questions about coursework (the required courses for vet school are very similar to the ones for med school, but there are a few anomalies at certain vet schools) and about applying to vet school. When it comes time to apply (your junior summer if you’re hoping to matriculate right after graduation, or your senior summer if you’re taking one glide year), we’ll work with you on application logistics. You’re always welcome at the programming we offer for pre-meds, such as the Interviewing Info Session or the session we do on writing a personal statement for your application, since the vet school application process is very similar to the med school one. The key differences are in timing and your letters of recommendation. You will need 3-4 individual recommenders who will complete forms via VMCAS, the application service that most (but not all!) vet schools use. The committee letter process through HPA is optional – vet schools do not expect committee letters in the way that medical schools do. You’ll also submit your application in the fall rather than early summer. The AAVMC website and their pre-vet newsletters may provide particular advice, so we’d recommend bookmarking that site, as well as using our HPA resources, and be sure to contact Princeton’s Pre-Veterinary Society officers to be part of the pre-vet student community on campus. In any case, we’d like to meet you and talk about your pre-vet path in general, so please don’t be a stranger!

What veterinary opportunities exist at Princeton?

Veterinary experiences are essential because some schools require that you have a minimum number of veterinary hours while others have a recommended minimum number of hours. Experiences also allow you to work alongside veterinarians, who are valuable resources for understanding vet school and the vet medicine field. They may even be willing to write you letters of recommendation, which are an important component of your vet school application.

Since Princeton does not have its own veterinary or medical school, opportunities are frankly limited compared to for example, Cornell, which does have both professional schools. However, you could still make the best of your Princeton and college experience by taking advantage of related opportunities both near campus and in your hometown. It is imperative that you take initiative. Here are some initial steps you can take:

- The HPA newsletter occasionally has links to veterinary opportunities so keep a lookout for those HPA emails. Sign up for individual vet school newsletters as well.

- To gain animal experience, you can volunteer or foster animals through your local animal shelter or even through SAVE A Friend to Homeless Animals, which is a shelter that is a 10-15 minute drive from campus. The PACE center organization SVC TigerTails occasionally organizes trips to volunteer at the shelter near Princeton, but it remains largely inactive due to transportation limitations. You will likely have to take initiative.

- Contact local veterinary clinics in or near your hometown via both phone and email for a summer shadowing experience or even a paid job as a veterinary assistant, though the latter is much more difficult (but not impossible!) to secure since clinics would prefer more experienced job-seekers. It’s always going to be difficult to get your foot in the door when searching for your first veterinary experience. It takes a lot of persistence, luck, and dozens of unreplied emails. Make an excel sheet and keep track all of the places you contact. Don’t give up hope and it’s never too late to get started!

- There are also veterinary clinics in the Princeton area such as the Princeton Animal Hospital & Carnegie Cat Clinic that you can contact to volunteer/shadow/work with during the school year. Unfortunately, they aren’t located at a walking distance and you will likely have to either drive, bike, or take a bus. A potentially cheaper option is taking the free TigerTransit weekend shopper to either the Wegmans or Walmart stop, which are located at a walking distance from a few other clinics. Be resourceful and creative 😉

- Use the TigerNet Alumni Directory to look up alumni that are currently in the veterinary medicine field. Log in with your netID, click on CAREER SEARCH on the left sidebar and select Veterinary Medicine as the field/specialty. You could try reaching out the contacts near your areas if there are any for veterinary opportunities!

- Many vet schools consider biomedical/science research experiences to be important. Taking up a position as a research assistant in a NEU/EEB/MOL department is one avenue you may want to explore since there are A TON of research opportunities at Princeton. You can cold email professors about your interests, why you would make a valuable addition to their lab, and what you find fascinating about their research. Thesis work related to the biological sciences would also be considered valuable to vet schools so making sure your independent work is impressive and impactful is another way to shine.

- Clubs, extracurriculars, and service work are also valuable to vet schools because they show that you are a well-rounded applicant. Leadership and interpersonal skills are important for future vets so try to get involved with student organizations. You do NOT have to join twenty clubs, you do NOT have to be president of all the clubs that you’re a part of, and you do NOT have to participate in exclusively animal-related activities. DO be yourself, get out of your comfort zone, and pursue what you’re passionate about and is meaningful to you!

- Did you know there are also vets on campus?! Dr. Laura Conour and Dr. Grace Barnett are research veterinarians in LAR (Laboratory Animal Resources) and are contacts you may want to consider reaching out to for animal/veterinary opportunities in lab animal medicine: https://www.princeton.edu/news/2018/08/08/meet-laura-conour-princetons-research-veterinarian,https://ria.princeton.edu/news/laboratory-animal-resources-welcomes-staff-veterinarian-grace-barnett,https://research.princeton.edu/people/laura-conour

- You may be able to utilize Princeton’s various funding sources to develop and fund your own veterinary/animal/research internship through PEI student initiated internships, the Streicker International Fellows Fund, ProCES, etc. Sometimes, IIP has the occasional veterinary clinic internship abroad so check their website out.

- There are also short, immersive (and usually pricey) programs that host college students at vet schools to help them learn more about the lives of vet school students and the field. Schools with these programs include Tufts, UPenn, and UCDavis.

- This is intuitive, but if you are interested in non-standard veterinary experiences (wildlife, zoo, emergency, community medicine, shelter medicine, equine, large animal, etc), you will have to put in many many hours searching for opportunities online. Summer opportunities are especially competitive. Always keep searching for opportunities. Bookmark or keep a list of ones you find interesting and want to apply to soon or a few years down the line.

- Sometimes students may have to work extra jobs to cover their education costs at Princeton, which may deter them from pursuing veterinary experiences. Unfortunately, many veterinary opportunities are usually not funded and/or are unpaid. While you should still try to aim for a couple hundred veterinary hours and to get at least one veterinarian recommendation, vet schools offer you the opportunity to explain circumstances in which you could not gain as much experience as you would have liked to. Reach out to HPA to determine how best to explain your circumstances in your VMCAS application.

How can I meet other pre-vet students?

Since campus life will no longer be the same during the 2020-2021 academic year, organizations must find alternative ways to allow students to meet and stay connected with one another. We are currently planning virtual events for the upcoming year so stay tuned!